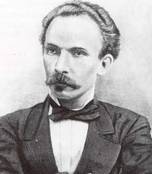

De Cubaanse dichter en schrijver José Martí (1853-1895) leidde in de negentiende eeuw de Cubaanse onafhankelijkheidsbeweging. Was zowel een inspiratiebron voor Che Guevara als Fidel Castro.

José Martí wordt op 28 januari 1853 geboren in Havana als de zoon van de Catalaans Spaanse Mariano Martí Navarro. Zijn moeder, Leonor Pérez Cabrera, is afkomstig van de Canarische Eilanden. Martí is de eerste zoon die zijn ouders samen krijgen. Na hem volgen er nog zes broers. Als Martí vier is verhuist het gezin naar de Spaanse stad Valencia. Twee jaar later keert het gezin echter alweer terug en volgt de jonge Martí een opleiding aan een openbare school.

Martí ontwikkelt zich tot journalist, schrijver, dichter en vertaler. Daarnaast houdt hij zich bezig met schilderen. In 1867 begint hij met het volgen van lessen aan de school voor kunsten in Havana. Erg succesvol is Martí, tot zijn eigen teleurstelling, echter niet in het schilderen. Commercieel levert het hem weinig tot niets op.

In 1869 publiceert José Martí voor het eerst een politiek getinte tekst in een krant, de El Diablo Cojuelo. Hetzelfde jaar schrijft hij de beroemd geworden tekst 10 de octubre. In dit sonnet schrijft Martí over de gebeurtenis die zich op 10 oktober 1868 op Cuba voordeed. Landeigenaar Carlos Manuel de Céspedes riep zijn mede-Cubanen toen op zich te verzetten tegen de Spaanse overheersing. Op Cuba is 10 oktober tegenwoordig nog altijd een feestdag. Het sonnet van Martí over de gebeurtenis wordt later gepubliceerd in zijn schoolkrant.

Als de koloniale autoriteiten op Cuba in maart 1869 de scholen sluiten, kan Martí zijn opleiding niet voorzetten. Het is een van de redenen waarom Martí antipathie ontwikkelt tegen de Spaanse bezetting van zijn geboorteland. Ook is hij fel tegenstander van de slavernij die op het eiland wordt gepraktiseerd.

Martí steekt zijn protesten tegen het beleid van de Spaanse kolonisator niet onder stoelen en banken en wordt op 21 oktober 1869 gearresteerd. De Spanjaarden beschuldigen hem van verraad tegen de overheid. Spanje zit in die periode niet te wachten op kritiek. Dit mede door een onafhankelijkheidsopstand die kort daarvoor is uitgebroken in de Cubaanse regio Oriente. Martí wordt veroordeeld tot een gevangenisstraf van zes jaar. Tijdens zijn slotpleidooi claimt de veroordeelde Cuba’s recht op onafhankelijkheid.

In de gevangenis wordt Martí ziek. De kettingen die aan zijn benen bevestigd zitten hebben grote schade aangericht. De overheid laat Martí dan overbrengen naar het Cubaanse gevangeneneiland Isla de la Juventud, dan nog Isla de Pinos genoemd. Enige tijd hierna wordt Martí verbannen naar Spanje.

Ballingschap

Tijdens de jaren dat Martí als balling in Spanje verblijft, schrijft hij nog meer artikelen over de misdaden die Spanje volgens hem pleegt in zijn geboorteland Cuba. Daarnaast pakt hij zijn studies weer op en krijgt hij na enige tijd zijn burgerrechten weer terug. In 1878 reist hij in het geheim naar de Cubaanse hoofdstad Havana en accepteert daar een baan. Een jaar later wordt hij echter gearresteerd en opnieuw gedeporteerd naar Spanje. Zijn vrouw en kort daarvoor geboren zoon, Jose Francisco, blijven achter op Cuba.

Na weer enige tijd in Spanje te hebben gewoond, verhuist Martí in 1881 naar New York waar hij zich onder meer inzet voor de belangen van Uruguay, Paraguay en Argentinië. In de tussentijd mobiliseert hij de Cubaanse ballingen, in het bijzonder die in de Amerikaanse staat Florida. Hij doet dit omdat hij zo een revolutie op Cuba wil ontketenen. Zijn doel: een onafhankelijk Cuba. Sommige Amerikaanse politici spreken zich in die tijd uit voor een Amerikaanse annexatie van Cuba. Martí is hier fel tegen en laat dit de Amerikaanse politici tijdens lobbywerk duidelijk weten.

Een poging om in 1894 Cuba binnen te vallen en te vechten voor onafhankelijkheid mislukt. Martí en zijn mannen worden in Florida gestopt. De Cubaan laat zich hierdoor echter niet uit het veld slaan. Op 25 maart 1895 publiceert hij samen met de rebellerende generaal Máximo Gómez het Manifesto of Montecristi. In dit manifest wordt de onafhankelijkheid van Cuba uitgeroepen en een eind gemaakt aan het wettelijk onderscheid tussen verschillende rassen.

Samen met een groep rebellen en leden van het leger van generaal Máximo Gómez landt Martí op 11 april 1895 op Cuba. De rebellenleider wordt op 19 mei dat jaar door de Spanjaarden gedood tijdens de Slag van Dos Ríos.

Na zijn dood is José Martí uitgegroeid tot een van de martelaren van de Cubaanse onafhankelijkheidsstrijd. Ook zijn gedichten zijn in de loop der tijd zeer beroemd geworden. In talloze Cubaanse steden en dorpen zijn (borst)beelden van Martí te vinden.

Boek: José Martí – Een oprecht mens

Montecristi Manifesto

De Engelse tekst van het Montecristi Manifesto:

Cuba’s revolution of independence, initiated in Yara, has now, after a glorious and bloody preparation, entered a new period of war, by virtue of the order and agreements of the Revolutionary Party both in and outside the Island, and of the exemplary presence within that party of all elements consecrated to the betterment and emancipation of the country, for the good of America and of the world. Without usurping the accent and declarations that are appropriate only to the majesty of a fully constituted republic, the elected representatives of the revolution that is reaffirmed today recognize and respect their duty to repeat before the patria, which must not be bloodied without reason or without just hope of triumph, the precise aims, born of good judgment and foreign to all thought of vengeance, for which the inextinguishable war that today in moving and prudent democracy leads all elements of Cuban society into combat was initiated and will reach its rational victory.

In the serene minds of those who represent it today and the responsible public revolution that elected them, this war is not the insane triumph of one Cuban party over another, or even the humiliation of a group of mistaken Cubans, but the solemn demonstration of the will of a country that endured far too much in the previous war to plunge lightly into a conflict that can end only in victory or the grave, without causes sufficiently profound to overcome human cowardice and its several disguises, and without a determination so estimable-for it is certified by death-that it must silence those less fortunate Cubans who do not have equal faith in the capacities of their nation or equal valor by which to emancipate it from its servitude.

This war is not a capricious attempt at an independence that would be more fearsome than useful-which only those who manifest the virtuous aim of conducting it to a more viable and certain independence can stave off or do away with, and which must not in truth tempt a people that cannot endure it-but the disciplined product of the resolve of solid men, who in the repose of experience have decided to face once more the dangers they well know, and of a cordial assembly of Cubans of the most diverse origins, all convinced that the virtues necessary for the maintenance of liberty are better acquired in the conquest of liberty than in abject dispiritedness.

This is not a war against the Spaniard, who, secure among his own children and in his deference to the patria they win for themselves, will enjoy, respected and even beloved, the liberty that will sweep away only those imprudent individuals who seek to block its path. This war will not be a cradle of tyranny or of disorder, which is alien to the proven moderation of the Cuban spirit. Those who promoted it, and who can still raise their voices and speak, affirm in its name, before the patria, their freedom from all hatred, their fraternal indulgence toward timid or mistaken Cubans, their radical respect for the dignity of man, which is the catalyst of combat and the cement of the republic, and their certainty that this war can be conducted in a way that contains the redemption that inspires it, and the ongoing relations in which a people must live among others, alongside the reality of what war is. They must express, as well, their categorical determination to respect, and to ensure that all respect, the neutral and honorable Spaniard during and after the war, and to be merciful toward the repentant, and inflexible only toward vice, crime, and inhumanity. In the war that has just begun again in Cuba the revolution does not see cause for a jubilation that could commandeer an unreflecting heroism, but only the responsibilities that must preoccupy the founders of nations.

Cuba is embarking upon this war in the full certainty, unacceptable only to halfhearted, sedentary Cubans, of the ability of its sons to win a victory through the energy of the thoughtful and magnanimous revolution, and the ability of the Cuban people, developed during those ten early years of sublime fusion and in the modern practices of work and government, to save the patria at its origin from the trials and troubles that were necessary at the beginning of the century in the feudal or theoretical republics of Hispano-America, which were without communication and without preparation. Inexcusable ignorance or perfidy it would be to remain unaware of the often glorious and now generally remedied causes for those American upheavals, which arose from the error of trying to adapt foreign models of uncertain dogma, related only to their place of origin, to the ingenious reality of countries that knew nothing of liberty except their own eagerness to attain it and the pride that they won while fighting for it.

The concentration of a merely literary culture in the capitals, the erroneous adherence of the republics to the lordly habits of the colony, the creation of rival caudillos as a consequence of the distrustful and inadequate treatment of remote areas, the rudimentary state of the only industry, which was farming or cattle herding, and the abandonment and distain of the fertile indigenous race amid the disputes between creed or locales that these causes for the upheavals in the nations of America carried on-these are in no way the problems of Cuban society. Cuba returns to war with a democratic and educated people, zealously aware of its own rights and those of others, and with even the humblest of its populace far more educated than the masses of plainsmen or Indians by whom, at the voice of the supreme heroes of emancipation, the silent colonies of America were transformed from herds of cattle into nations.

And the crossroads of the world, in the service of war and the foundation of a nationality, there come to Cuba, from their creating and conserving labor in the most capable nations of the globe and from their own efforts on behalf of the country’s persecution and misery, the lucid sons, magnates or servants, who after the first era of compromise between the heterogeneous components of the Cuban nation, which is now past, went forth to prepare, or on the Island itself continued preparing, by their own self-improvement, for the enhancement of the nationality to which today they bring toe soundness of their industrious persons and the certainty of their republican education.

The civic-mindedness of Cuba’s warriors, the skill and benevolence of her craftsmen, the real and modern employment of a vast number of her minds and fortunes, the peculiar moderation of the campesino seasoned by exile and war, the intimate and daily contact and rapid and inevitable unification of the diverse sectors of the country, the reciprocal admiration for the virtues equally distributed among Cubans who passed directly from the differences of slavery to the brotherhood of sacrifice, and the benevolence and growing capability of the freed slave, far more common than the rare examples of his deviation or rancor, all ensure Cuba, without unwarranted illusions, a future in which the conditions of stability and immediate labor for a fruitful people in a just republic will exceed those of dissociation and partiality stemming from the laziness or arrogance that war sometimes breeds, from the offensive rancor of a minority of masters stripped for their privileges, from the censurable haste with which a still invisible minority of discontented freed slaves might aspire, in disastrous violation of free will and human nature, to the social respect that solely and surely must come to them by their proven equality of talent and virtue, or from the sudden and widespread loss by the literate inhabitants of the cities of the relative sumptuousness or abundance that they derive today from the colony’s immoral and facile sinecures and the positions that liberty will cause to disappear.

A free nation, where work is open to all, positioned at the very mouth of the rich and industrial universe, will without obstacle and with some advantage replace, after a war inspired by the purest self-sacrifice and carried out in keeping with it, the shameful nation where well-being is obtained only in exchange for an express or tacit complicity with the tyranny of the grasping foreigners who bleed and corrupt it. We have no doubts about Cuba or its ability to obtain and govern its independence, we who, in the heroism of death and the silent foundation of the patria, see continually shining forth among the great and the humble its gifts of harmony and wisdom, which are only imperceptible to those who, living outside the real soul of their country, judge it, in their own arrogant concept of themselves, to possess no greater power of rebellion and creation than that which it timidly displays in the servitude of its colonial tasks.

And there is another fear from which cowardice, disguised as prudence, may wish to profit just now: the senseless and, in Cuba, always unjustified fear of the black race. The revolution, with all its martyrs and generous subordinate warriors, denies indignantly, as the long experience of those in exile and those on the island during the truce denies, the slanderous notion of a threat by the Negro race, which has been wickedly employed to the benefit of those who profit from the Spanish regime to stir up fear of the revolution. There are already Cubans in Cuba, of one color or another, who have forgotten forever-through the emancipating war and the work they carry on together-the hatred by which slavery may have divided them. The novelty and asperity of social relations following the sudden transformation of the man who belonged to another into his own man are less important than the sincere esteem of the white Cuban for the equal soul, painstaking education, freeman’s fervor, and lovable character of his black compatriot.

And if vile demagogues are born to the race, or avid souls whose own impatience incites that of their race, or in whom pity for their own people is transformed into injustice toward others, then out of their gratitude and prudence and love for the patria, out of their conviction of the need to disprove by a manifest demonstration of the intelligence and virtue of the black Cuban the still prevailing opinion of his incapacity for those two qualities, and in their possession of all the reality of human rights and the consolation and strength of their esteem for whatever element of justice and generosity there is in the white Cubans, the black race itself will expatriate the black menace in Cuba without a single white hand having to be raised to the task. The revolution knows this and proclaims it; those in exile proclaim it as well.

The Cuban black has no schools of wrath there, and in the war not a single black was punished for arrogance or insubordination. Upon the shoulders of the black man, the republic, which he has never attacked, moved in safety. Only those who hate the black see hatred in the black, and those who traffic in such unjust fears do so in order to subjugate the hands that could be raised to expel the corrupting occupier from Cuban soil.

From the Spanish inhabitants of Cuba, the revolution, which neither flatters nor fears, hopes to receive, instead of the dishonorable wrath of the first war, such affectionate neutrality or truthful assistance as to make the war shorter, its disasters lesser, and the peace in which fathers and sons must live together easier and friendlier. We Cubans are starting the war, and Cubans and Spaniards will finish it together. If they do not mistreat us, we will not mistreat them. If the show respect, we will respect them. The blade is answered with the blade, and friendship is answered with friendship. There is no hatred in the Antillean bosom, and in death the Cuban salutes the brave Spaniard who was torn by the cruelty of forced military service from his home and his land to come and murder in manly breast the liberty that he himself yearns for. More than saluting him in death, the revolution would like to welcome him in life, and the republic will be a tranquil homeland for however many hardworking and honorable Spaniards wish to enjoy the liberty and well-being within it that they will not find for a long time to come in the torpor, apathy, and political vices of their own land. This is the heart of Cuba, and in this way will the war be carried out. What Spanish enemy will the revolution truly have? Will it be the army, republican for the most part, which has learned to respect our valor as we respect theirs, and sometimes feels a greater impulse to join us than to do battle with us? Will it be the conscripts, already versed in the ideals of humanity and opposed to spilling the blood of their equals for the benefit of a useless scepter or a greedy patria, the conscripts who were cut down in the flower of their youth to come and defend-against a people that would happily welcome them as free citizens-an unstable throne that presides over a nation sold by its leaders? Will it be the mass of craftsmen and clerks, now after their years in Cuba, humane and educated, who, on the pretext of defending the patria, were dragged yesterday into ferocity and crime by the interests of the wealthy Spaniards who now, with most of their fortunes safe in Spain, evince less zeal than when they bloodied the land of their riches after war found them with all their fortune there? Or will it be the founders of Cuban families and industries, vexed and oppressed like the Cubans and weary by now of the deceptions of Spain and its misrule, who, ungrateful and imprudent, with no thought for the peace of their homes and the preservation of a wealth that the Spanish regime threatens more than any revolution, turn against the land that has transformed them from sad peasants into happy husbands and fathers of an offspring capable of dying without hatred to ensure for their bloody father a free land at the end of the permanent discord between the criollo and those born on the Peninsula, a land where an honorable fortune can be maintained without bribery and amassed without anxiety and where the son does not see, between his kiss and his father’s hand, the abhorrent shadow of the oppressor?

What fate will the Spaniards choose: relentless war, open or concealed, that threatens and further disturbs the country’s perennially turbulent and violent relations, or definitive peace, which will never be achieved in Cuba except by independence: Will the Spaniards who have roots in Cuba provoke a war in which they may be vanquished? And by what right would the Spaniards hate us, when we Cubans do not hate them? The revolution makes use of this language without fear because the mandate to emancipate Cuba once and for all from the irremediable ineptitude and corruption of the Spanish government, and to open it forthrightly to all men of the new world, is as absolute as our will to welcome to Cuban citizenship, without faint hearts or bitter memories, the Spaniards who in their passion for liberty help us to victory in Cuba, as well as those other Spaniards who by their respect for today’s war redeem the blood that in yesterday’s war coursed, under their blows, from the chests of their sons.

The forms the revolution takes will provide no pretext for reproach to the vigilant cowards, fully aware of its selflessness, who in the formal errors or scant republicanism of the nascent country might have found some reason for which to deny it the blood they owe it. Pure patriotism will have no cause to fear for the dignity and future fate of the patria. The difficulty of America’s wars of independence and of its first nationalities has not lain primarily in any discord among its heroes or the emulation and mistrust inherent in mankind, but rather in the lack of a form that could contain both the spirit of redemption which, supported by lesser incentives, promotes and nourishes the war, and the practices necessary to war, which the war must sustain and not encumber. In its initiatory war, a country must find a manner of government that can satisfy both the mature and cautious intelligence of its literate sons and the necessary conditions for the assistance and respect of its other peoples, and that does not hinder but enables the full development and rapid conclusion of the war that was calamitously necessary to the public happiness. From its origin, the patria must be constituted in viable forms, forms born of itself, so that a government without reality or sanction does not lead it into biases or tyranny.

Without impinging by an unrestrained concept of its duty upon the integral faculties of constitution by which, in their peculiar responsibility before the liberal and impatient contemporary world, the country’s educated and uneducated elements are ordered and reconciled-both equally moved by executive impetus and ideal purity, and with identical nobility and the unassailable title of their blood, to hurl themselves after the guiding soul of the first heroes and open an industrious republic to humanity-the Cuban Revolutionary Party can do no more than legitimately declare its faith that the revolution will find forms that will guarantee it, in the unity and vigor indispensable to a civilized war, the enthusiasm of the Cuban people, the trust of the Spaniards, and the friendship of the world.

To know and establish reality, to form in a natural mold the reality of the ideas that produce or extinguish deeds and the reality of the deeds that are born from ideas, to organize the revolution with dignity, sacrifice, and culture so that no man’s dignity is harmed, and the sacrifice does not strike a single Cuban as futile, to ensure that no Cuban sees the revolution as inferior to the country’s own culture or to the foreign, unauthorized culture that has alienated the respect of virile men by the inefficacy of its results and the doleful contrast between the current pusillanimity of its sterile possessors and their arrogance, but that all Cubans perceive it, rather, as based in a profound knowledge of man’s endeavor to rescue and maintain his dignity-these are the duties and intentions of the revolution. It will be governed to ensure that a powerful and effective war will quickly establish a stable home for the new republic.

The war, healthy and vigorous from the start, which Cuba begins again today, with all the advantages of its experience and victory at last guaranteed to the unyielding resolve and lofty efforts of its unfading heroes, whose memory is always blessed, is not merely a pious longing to give full life to the nation that, beneath the immoral occupation of an inept master, is crumbling and losing its great strength both within the suffocating patria and scattered abroad in exile. This war is not an inadequate drive to conquer Cuba, for political independence would have no right to ask Cubans for their help if it did not bring with it the hope of creating one patria more for freedom of thought, equality of treatment, and peaceful labor.

The war of independence in Cuba, the knot that binds the sheaf of islands where shortly the commerce of the continents must pass through, is a far-reaching human event and a timely service that the judicious heroism of the Antilles lends to the stability and just interaction of the American nations and to the still unsteady equilibrium of the world. It honors and moves us to think that when a warrior for independence falls on Cuban soil, perhaps abandoned by the heedless or indifferent peoples for whom he sacrifices himself, he falls for the greater good of mankind, for the confirmation of a moral republicanism in America, and for the creation of a free archipelago through which the respectful nations will pour a wealth that must, at its passage, spill over into the crossroads of the world. Hardly can it be believed that with such martyrs and such a future there could be Cubans who would bind Cuba to the corrupt and provincial monarchy of Spain and its sluggish, vice-ridden wretchedness! Tomorrow the revolution will have to explain anew to its country and to the nations the local causes, universal in concept and interest, by which for the progress and service of humanity the emancipating nation of Yara and Guáimaro begins again a war that, in its unswerving idea of the rights of man and its abhorrence of sterile vengeance and futile devastation, deserves the respect of its enemies and the support of the nations.

Today, as we proclaim from the threshold of the earth, in veneration of the spirit and doctrines that produce and animate the wholehearted and humanitarian war for which the people of Cuba unite once more, invincible and indivisible, it is fitting that we evoke, as guides and helpers to our people, the magnanimous founders whose labor the grateful country takes up once again, and the honor that must prevent Cubans from wounding by word or deed those who gave their lives for them. And thus, making this declaration in the name of the patria and deposing before her and her free faculty of constitution the identical labor of two generations, the Delegate of the Cuban Revolutionary Party, created to organize and support the current war, and the Commander in Chief elected by all the active members of the Liberating army, in their shared responsibility to those they represent and in demonstration of the unity and solidity of the Cuban revolution, sign this declaration together.

José Martí

Máximo Gómez